Spiritual

A Spiritual Guide to the Dream World

We spend nearly one-third of our lives sleeping and we can’t function physically without it. But I’ve often wondered if there is also a spiritual reason we need to sleep — and dream.

Does our need for sleep coincide with a desire to enter a world where the spirit can roam free without the limitations of the physical body? Dreams are one of the most fascinating phenomena that we experience in our lives, and the Baha’i writings have an answer for every question I’ve ever had about this subject.

Baha’u’llah, the prophet and founder of the Baha’i Faith, wrote that “God embraceth worlds besides this world, and creatures apart from these creatures.” He explained that the world we live in while we’re awake is completely different and separate from the dream world, which is within us and has “neither beginning nor end.”

Baha’u’llah wrote that when our spirits transcend “the limitations of sleep” and detach from “all earthly attachment,” God lets us travel throughout “a realm which lieth hidden in the innermost reality of this world.” In this dream realm, there may be messages to meditate on and secrets to discover.

It’s fascinating to think of what traveling looks like without physical means. When we are awake, there is a limit to how fast we can travel on public transportation, but, according to the Baha’i writings, we can travel throughout the planet “in sleep, in the twinkling of an eye.” In the early 1900s, Abdu’l-Baha, the son of Baha’u’llah and his designated successor and interpreter of the Baha’i writings, called this “spiritual traveling.”

Abdu’l-Baha explained, “In the time of sleep this body is as though dead; it does not see nor hear; it does not feel; it has no consciousness, no perception—that is to say, the powers of man have become inactive, but the spirit lives and subsists. Nay, its penetration is increased, its flight is higher, and its intelligence is greater.”

It seems like our spiritual powers and abilities are limitless when we dream. To help us understand this freedom we have when our physical bodies are not in charge, Abdu’l-Baha used the analogy of a bird in a cage: “Our body is like the cage, and the spirit is like the bird. We see that without the cage this bird flies in the world of sleep; therefore, if the cage becomes broken, the bird will continue and exist. Its feelings will be even more powerful, its perceptions greater, and its happiness increased.”

Abdu’l-Baha further explained the powers and freedoms our spirits have in the dream world. He said, “in the state of sleep without eyes it sees; without an ear it hears; without a tongue it speaks; without feet it runs.”

So, how much importance should we place on the events that take place in our dreams? If our perceptions and intelligence are greater in this state, can our dreams provide us with worthy insight into the future?

When asked about the immortality of the spirit, Abdul-Baha referenced dreams. He said:

“How often it happens that it [the spirit] sees a dream in the world of sleep, and its signification becomes apparent two years afterward in corresponding events. In the same way, how many times it happens that a question which one cannot solve in the world of wakefulness is solved in the world of dreams. In wakefulness the eye sees only for a short distance, but in dreams he who is in the East sees the West. Awake he sees the present; in sleep he sees the future.”

I know I’ve had dreams that predicted my father’s health scare, and other dreams that predicted the birth of some of my nieces and nephews. Dreams can serve as warnings, reminders, or exciting glimpses into the future. But how can we know which dreams will come true and which won’t? I know I go through times when many of my dreams seem like they could have a lot of merit, and other times, it feels like everything I’m dreaming is complete nonsense. So, is it something we are doing wrong? Do we have control over the accuracy of our dreams?

The Baha’i writings tell us there is no doubt that “truth is often imparted through dreams” but at the same time, dreams and visions are always “influenced more or less by the mind of the dreamer and we must beware of attaching too much importance to them.”

In a letter written in 1925 on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Baha’i Faith, he wrote, “The purer and more free from prejudice and desire our hearts and minds become, the more likely is it that our dreams will convey reliable truth, but if we have strong prejudices, personal likings and aversions, bad feelings or evil motives, these will warp and distort any inspirational impression that comes to us.”

So, he advised us to strive to “become pure in heart” and detached from everything that is not good and godly. Then, he wrote, “our dreams as well as our waking thoughts will become pure and true.”

Just because some dreams won’t come true, it doesn’t mean they can’t be coherent, relaxing, or exciting. But, sometimes we have delusions or nightmares — bad dreams that are uncomfortable, scary, or stressful. After speaking with Abdu’l-Baha about dreams, Mrs. May Maxwell, an early American Baha’i, said her conversation with him led her to understand that these dreams result from “various influences like fatigue, fear, etc.” These confusing dreams are created when our bodies influence our souls‚ as opposed to our souls influencing our bodies.

Abdu’l-Baha said that we have three kinds of dreams, and the confused dream is the one type of dream that has no truth or significance. For example, Abdu’l-Baha said, “during the day a man becomes engaged in a quarrel and dispute. Later, in the world of the dream, these same circumstances appear to him. This is a confused dream. It has no interpretation and contains no discoveries. Before the person dreamed, he was overcome with delusions. It is clear that this kind of dream bears no interpretation and is confused.”

As a Baha’i, it gives me so much solace and comfort to know that, as Abdu’l-Baha explained, although “Those who have ascended have different attributes from those who are still on earth, yet there is no real separation.” Since time is an illusion while we are in this earthly realm, what we know of as time does not exist in the afterlife. In addition, prayer helps our spirits transcend the physical limitations we have and connect to our angels and ancestors while we are still here.

Abdu’l-Baha said, “In prayer there is a mingling of station, a mingling of condition. Pray for them as they pray for you! When you do not know it, and are in a receptive attitude, they are able to make suggestions to you, if you are in difficulty. This sometimes happens in sleep.” So, if we pray before we go to bed and are receptive to the wisdom of those who have come before us, we just may meet them and receive guidance in the world of dreams.

Indeed, Abdu’l-Baha wrote, “When thou desirest and yearnest for meeting in the world of vision; at the time when thou art in perfect fragrance and spirituality, wash thy hands and face, clothe thyself in clean robes, turn toward the court of the Peerless One, offer prayer to Him and lay thy head upon the pillow. When sleep cometh, the doors of revelation shall be opened and all thy desires shall become revealed.”

Source link

If We’re Spiritual Beings, Why Do We Live in a Physical World?

During my half-century as a university professor and publishing scholar, I devoted a good deal of time to an obvious but puzzling question: If we presume an omnipotent Creator exists, why did He decide to give a physical dimension to His creation?

Or, stated in more personal terms, if the creation of human beings lies at the heart of the purpose of physical reality—as most religions suppose—then why did the Creator decide that we would benefit from waking up in an environment where we think we are physical beings, when we really aren’t; where we think we own stuff, when we actually don’t; and where we seem to constantly worry about dying, when our conscious self together with all our essential human powers will endure forever as properties of our eternal soul?

My first attempt to get to the heart of this question, a book entitled The Metaphorical Nature of Physical Reality, discussed the premise that physical reality is a poetic or metaphorical expression of abstract virtues and, as such, provides a foundational methodology for human beings to become introduced to a higher, nobler, and more permanent spiritual reality.

In this work, I applied the terms and techniques of literary studies, which describe how metaphor works, to demonstrate that analogical processes provide a useful means for the human mind to be introduced to, acquire, and understand ephemeral or metaphysical realities—making it possible for us to approach the entire physical part of our lives as a dramatic teaching device.

RELATED: The Physical World: One Great Parable of Life

My next book-length study of this subject, The Purpose of Physical Reality: The Kingdom of Names, dealt with the way in which physical reality and our experience in it might correctly be described as a classroom where we prepare for the continuation of personal development after the dissociation of our selves—our soul with all its complement of powers and faculties—from our physical body.

This work concludes by observing that one of the really useful devices this classroom offers us as preparation for that transition—we might think of it as a workshop or “breakout” session—is aging, an ingeniously devised experience in which we gradually watch our skin become wrinkled, feel our joints falter, our organs failing, and the whole organic physical construct become incrementally more dysfunctional until it dies, decomposes, and, according to Walt Whitman, becomes “leaves of grass,” or, in my own case, a bit of crab grass.

The next stage in my study of physical reality as an expression of a coherent and logically structured expression of a divine plan for human education was The Arc of Ascent: The Purpose of Physical Reality II. The central thesis of this book—that individual spiritual development in the context of the physical classroom is inextricably linked to our reality as inherently social beings—led me to the conclusion that all individual virtue is largely theoretical until practiced and developed in the context of human relationships.

For example, a hermit dwelling in a mountain cave may consider himself to be extremely mystical and spiritual, completely kind and selfless, but neither he nor we can be sure he has acquired such virtues unless and until he emerges from his seclusion to help somebody, not once, but enough times that his theoretical virtues become habituated and thus integral attributes of his character.

The thesis of the series of essays you’re reading now came from ideas developed in my third assault on this endlessly fascinating question, entitled Close Connections: The Bridge between Spiritual and Physical Reality. As the title implies, this lengthy and complex discourse analyzes how the gap between the metaphysical and physical aspects of reality is bridged constantly and bi-directionally on both the cosmic and the individual level. Stated axiomatically, this work compares the theory that an essentially unknowable metaphysical being—the Creator—runs physical reality, with the parallel theory that an essentially knowable metaphysical being—the human soul—operates the human body.

RELATED: Why Do Spiritual Beings Need a Physical World?

As Abdu’l-Baha so clearly pointed out in a talk he gave in Paris, God employs His messengers as intermediaries between Himself and physical reality, even as we employ our brains as intermediaries between our “essential self” and our bodies:

Like the animal, man possesses the faculties of the senses, is subject to heat, cold, hunger, thirst, etc.; unlike the animal, man has a rational soul, the human intelligence, whereby he can think abstractly, or meditate and reflect on philosophical or theological questions.

This intelligence of man is the intermediary between his body and his spirit.

When man allows the spirit, through his soul, to enlighten his understanding, then does he contain all Creation; because man, being the culmination of all that went before and thus superior to all previous evolutions, contains all the lower world within himself. Illumined by the spirit through the instrumentality of the soul, man’s radiant intelligence makes him the crowning-point of Creation.

If this thesis is correct, even as you at this moment read this essay, you and I are conversing soul-to-soul by means of a series of intermediaries.

The written expression of ideas emanated from my conscious mind through the intermediary of my brain. It was then published here at BahaiTeachings.org, and is at this moment being translated by your senses into abstract concepts through the capacity of your brain, which then transforms the complex of symbols that constitute human language into meaning.

Your conscious mind then considers these ideas, and either rejects them as unworthy of being retained or stores them in the repository of your memory and the convictions of your inner being.

So, to put it in terms that contemporary physics might find appealing: how can we defend the thesis that essentially metaphysical beings—and therefore, for the majority of contemporary scientists, nonexistent beings—think themselves capable of operating heavy machinery without hurting anyone?

In Close Connections I discuss critical questions related to evolution, particle physics, astrophysics, history, cosmology, anthropology, medicine, physiology, psychiatry, and all sorts of other fields directly affected by the assertions that metaphysical reality exists and, more important, that there is a strategic and systematic interplay between the metaphysical and physical aspects of reality. Most important in this study is the consideration that these relationships are at the heart of any understanding about how reality works at every level of existence.

My overall objective in Close Connections is to demonstrate an integrative view of reality provided in and corroborated by authoritative Baha’i texts. But since I cannot in a single series of essays discuss all the support for a thesis wrought over ten years, several books, and hundreds of pages of research, I have decided to focus here on one of the fundamental themes in that study: the relationship between the religious axiom that the human purpose is to love God, and the decision of the Creator to make the method by which we can attain this love relationship subtle, indirect, initially physical, poetic, and, consequently, largely hidden and concealed from intuitive knowledge.

In other words, how do we love God when we cannot possibly know the essential reality of God?

This represents a supremely difficult challenge—unless, of course, we are first led out of the cave of ignorance by mentors, and set on the path of willed, self-sustained progress, a process that translates well the Latin verb educare (to lead out) into the English cognate “to educate.”

Coupled with this idea is another equally enigmatic concept: love. Since, according to the Baha’i teachings, the human purpose is to learn to know and to worship God, or to love and to express that love in action, then it is crucial that we understand how both processes work, as neither learning nor loving can be coerced, even by God, because both require us to employ our free will, and our will cannot be free if it is coerced.

So please follow along in this series of essays as we explore what the Baha’i teachings recommend when they ask us to kindle the fire of divine love in our hearts and souls.

This series of essays is adapted from John Hatcher’s address to the 2005 Association for Baha’i Studies Conference titled The Huri of Love, which comprised the 23rd Hasan M. Balyuzi Memorial Lecture.

Source link

Is Caring For Your Mental Health a Spiritual Practice?

The Baha’i writings emphatically state that mental health struggles are separate from the life of the soul: “The soul of man is exalted above and is independent of all infirmities of the body or mind.” But there also appears to be a strong correlation between spiritual strength and mental health management.

Even as a mental health professional myself, I’m still seeking to understand the connection between spirituality and mental health, and learning how to apply the spiritual teachings of my faith to my life.

I have experienced anxiety and depression at different points of my life and have come to feel that perhaps such struggles are part of our spiritual journey in this life and preparation for the next. Going through bouts of anxiety and depression were a catalyst for me to reflect on my purpose. I found myself asking: Why am I experiencing these tests and difficulties? Have I done something wrong to deserve this?

At times, these questions led me to question how much I was serving my community and whether I was doing my part as a professional counselor to truly help my clients. They led me to examine my underlying prejudices, my fear of failure and my need to please others.

I have begun to grasp that some things are in my power to change and some are not. Some of my struggles may be biologically inherited, and some may be a consequence of the environments I find myself in — and I may never be able to differentiate between them. But as painful as such challenges can be, the challenges we face can provide opportunities to grow in areas such as patience, forbearance, and tolerance.

The central figures of the Baha’i Faith have shared some wisdom in this regard. In a 1911 speech, Abdu’l-Baha, the son of Baha’u’llah, the founder and prophet of the Baha’i Faith, said: “Test are benefits from God, for which we should thank Him. Grief and sorrow do not come to us by chance, they are sent to us by the Divine Mercy for our own perfecting.”

Coming to this understanding has led me on a path of discovering what virtues I need to work on to grow spiritually. I’m learning to be honest with myself as a human being, as a member of my faith community and as a professional — to acknowledge what I’m capable of, listen to my inner voice, and practice truthfulness, which Baha’u’llah told us is the “foundation of all human virtues.”

All the prophets of God endured intense persecution and needed to take time to focus on their own wellness, pray, and reflect. For example, Moses went to the mountain, and Christ went to the wilderness. And although these holy figures had spiritual power beyond our capabilities, they were human as well. Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Baha’i Faith, wrote:

“As we suffer these misfortunes we must remember that the Prophets of God Themselves were not immune from these things which men suffer. They knew sorrow, illness and pain too. They rose above these things through Their spirits, and that is what we must try and do too, when afflicted. The troubles of this world pass, and what we have left is what we have made of our souls; so it is to this we must look — to becoming more spiritual, drawing nearer to God, no matter what our human minds and bodies go through.”

Though there’s still stigma surrounding mental illness, it’s important that we move past those attitudes. Seeking help and support from a trained mental health professional can be essential. Therapy provides a safe and confidential space to explore any concerns a person may need to address, and furthermore, most clinicians today understand the importance of incorporating spirituality into their practice.

The skills used in therapy are fundamentally derivative of all spiritual traditions. They incorporate faith over fear as a coping skill, overcoming worries, changing anxious thoughts into peaceful ones, practicing grounding and mindfulness, strength-based methods, redirection, cognitive-behavioral approaches, and the idea that pure thoughts lead to pure actions.

When seeking an appropriate counselor, the initial intake interview can provide you with the opportunity to develop rapport with your clinician and determine if they respect your religious beliefs, and if they are open to using spiritual tools. Remember, the most essential spiritual quality is truthfulness: if you are not capable of being honest with your therapist, progress in counseling will be impossible.

Additionally, taking time to rely on the Divine remedy — the Word of God — has brought me much healing and helped me cope with my own mental health struggles. When we are in pain, we can lose sight that our faith in God can pull us through times of distress. I find comfort in one of my favorite quotes from the Baha’i writings:

“Rely upon God. Trust in Him. Praise Him, and call Him continually to mind. He verily turneth trouble into ease, and sorrow into solace, and toil into utter peace. He verily hath dominion over all things.”

Keeping our thoughts centered on prayer and the Word of God is critical, but we also have physical bodies that require training. Our minds benefit from exercise and training, which is why practices such as meditation and mindfulness better prepare us to be able to cope with the stressors of life.

Source link

The Spiritual Meaning and Significance of Spring

Every year, around the vernal equinox, the world seems to come alive. Depending on where you live in the Northern Hemisphere, trees and bushes that were once icy and barren begin to bear buds, leaves, flowers, or fruit. The grass becomes greener, hibernating animals come out to explore, and insects that were burrowed under the ground hatch from their eggs and emerge to the surface.

“In the spring there are the clouds which send down the precious rain, the musk-scented breezes and life-giving zephyrs; the air is perfectly temperate, the rain falls, the sun shines, the fecundating wind wafts the clouds, the world is renewed, and the breath of life appears in plants, in animals and in men,” said Abdu’l-Baha, one of the central figures of the Baha’i Faith. “Earthly beings pass from one condition to another.”

If all of this rebirth and renewal is happening during spring to every plant and animal in the world, what kind of spiritual transformation is happening to people?

The Significance of Spring for Our Spiritual Transformation

I remember my winter during the height of the coronavirus quite clearly…

Just like many other living beings, I spent the winter hibernating and staying cooped up indoors — because I had no interest in being out in the cold unless I had to, and I also happened to be a germaphobe during COVID-19. So, when the clouds disappeared, and the temperature finally hit 70 degrees, I couldn’t help but step outside and take a few long deep breaths. I inhaled and exhaled — the air was so sweet, I felt like I could taste it. As I walked and soaked in the warm heat of the sun, my body felt soothed, and my mind felt at ease. I knew that my spirit was being revived just like the rest of the world.

Abdu’l-Baha said it’s as if the Earth is dead and lifeless during the winter. But when spring comes, “it finds a new spirit, and produces endless beauty, grace and freshness. Thus the spring is the cause of new life and infuses a new spirit.”

I could feel that I was becoming alive with this new spirit. Of course, this spiritual regeneration and renewal didn’t happen like clockwork once the sun came out. I spiritually recuperated for 19 days from the beginning of March until the first day of spring – the Baha’i new year.

RELATED: Fasting: Spring Cleaning for the Soul

During these 19 days, Baha’is fast — we do not eat or drink anything from sunrise to sunset. But this abstention from food is merely symbolic and is, as Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Baha’i Faith, explained, “ a reminder of abstinence from selfish and carnal desires.”

He also wrote that the fasting period is “essentially a period of meditation and prayer, of spiritual recuperation, during which the believer must strive to make the necessary readjustments in his inner life, and to refresh and reinvigorate the spiritual forces latent in his soul. Its significance and purpose are, therefore, fundamentally spiritual in character.”

Every year during March, I make sure to prioritize my spiritual health and tune into my spirit. I engage in self-reflection, clarify what goals I’d like to accomplish in the coming year, and work on breaking old unwanted habits. I thank God for my blessings, ask forgiveness for my wrongdoings, and strive to cleanse and purify my heart and soul. That way, when I emerge from my hibernation, I feel both physically and spiritually refreshed and transformed.

“Jesus Christ said ‘Ye must be born again’ so that divine Life may spring anew within you,” said Abdu’l-Baha at a talk in Bristol, England in 1911.

Be kind to all around and serve one another; love to be just and true in all your dealings; pray always and so live your life that sorrow cannot touch you. Look upon the people of your own race and those of other races as members of one organism; sons of the same Father; let it be known by your behaviour that you are indeed the people of God. Then wars and disputes shall cease and over the world will spread the Most Great Peace.

The Spiritual Meaning of Spring for Humanity

Baha’is believe that world peace is not just a naïve hope or wishful thinking, but it is actually inevitable. We understand that the world is going through very turbulent and trying times, but as Shoghi Effendi wrote:

We stand on the threshold of an age whose convulsions proclaim alike the death-pangs of the old order and the birth-pangs of the new.

“The whole earth,” wrote Baha’u’llah, the prophet and founder of the Baha’i Faith, “is now in a state of pregnancy. The day is approaching when it will have yielded its noblest fruits, when from it will have sprung forth the loftiest trees, the most enchanting blossoms, the most heavenly blessings.”

Just like the Earth goes through different seasons and cycles, Baha’is believe that humanity goes through various stages of development. And in every stage, God sends Messengers (i.e., Zoroaster, the Buddha, Krishna, Moses, Jesus Christ, Mohammed, the Bab, and Baha’u’llah) to reveal more of His unfolding revelation to society.

Right now, humanity is in its turbulent adolescence age. But Baha’is believe that “when the impetuosity of youth and its vehemence reach their climax,” we will reach maturity and enter the stage of adulthood. We believe that the revolutionary teachings of Baha’u’llah — such as the equality of men and women, the harmony of science and religion, the elimination of the extremes of wealth and poverty, the abolition of all forms of prejudice, and the oneness of humanity — will help usher humanity towards maturity.

As Abdu’l-Baha wrote:

This period of time is the Promised Age, the assembling of the human race to the “Resurrection Day” and now is the great “Day of Judgment.” Soon the whole world, as in springtime, will change its garb. The turning and falling of the autumn leaves is past; the bleakness of the winter time is over. The new year hath appeared and the spiritual springtime is at hand.

The black earth is becoming a verdant garden; the deserts and mountains are teeming with red flowers; from the borders of the wilderness the tall grasses are standing like advance guards before the cypress and jessamine trees; while the birds are singing among the rose branches like the angels in the highest heavens, announcing the glad-tidings of the approach of that spiritual spring, and the sweet music of their voices is causing the real essence of all things to move and quiver.

This “spiritual spring” is so meaningful and significant because, as Abdu’l-Baha said, it’s the “age of spiritual awakening” where “the world has entered upon the path of progress into the arena of development, where the power of the spirit surpasses that of the body. Soon the spirit will have dominion over the world of humanity.”

Source link

Baha’is, the 1960s, and a Spiritual Revolution

The second Baha’i century began and World War II neared its end in 1944 — and the first second-century Baha’is were born. That generation made a major impact on the fortunes of the Baha’i Faith in the West.

Nineteen years later, in 1963, the first Universal House of Justice was elected by the world’s Baha’is, launching its initial plans for sharing the Baha’i teachings globally. During that period, the Baha’i Faith grew exponentially, fed by the fresh energy of a new and unique generation of youth. In its retrospective of the 20th century called “Century of Light,” the Universal House of Justice wrote:

No segment of the [Baha’i] community made a more energetic or significant contribution to this dramatic process of growth than did Baha’i youth … During the past hundred years our world underwent changes far more profound than any in its preceding history, changes that are, for the most part, little understood by the present generation. These same hundred years saw the Baha’i Cause emerge from obscurity, demonstrating on a global scale the unifying power with which its Divine origin has endowed it. As the century drew to its close, the convergence of these two developments became increasingly apparent.

RELATED: Yamamoto and Fujita: The First Japanese Baha’is

Babies born since 1944 began to come of age in the 1960s, deemed one of the top three decades of spiritual revival in history, because of its huge increase in the range of beliefs and worldviews.

I wanted to preserve the feelings experienced by this generation who became Baha’is during their teens and early twenties — those “second century believers” — who, after their independent searches for truth, accepted the Baha’i Faith. I gathered responses about their feelings and experiences during those unique times, including what attracted them, why they became Baha’is, and why they’ve remained in the Faith.

New trends emerged in the 1960s: environmentalism, second-wave feminism, all brought about by a youth counterculture that aimed to counteract materialism, racism, tradition, and war. In the United States, a youthful President Kennedy brought an energy that inspired the youth, challenging them to contribute to the public good by saying, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” The U.S. government created the Peace Corps, spurring young people to volunteer to altruistically serve in other countries.

People of color increasingly asserted their rights. In 1963, the African American civil rights leader Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered to a quarter million pro-civil rights demonstrators a speech envisioning a world where citizens would all live in racial harmony. The American Indian Movement formed in 1968 to support Indigenous people seeking to gain tribal sovereignty. Movements dedicated to freedom, equality, and peace flourished throughout the world.

When I reached out to those who had become Baha’is during that turbulent period in history, the respondents shared these thoughts:

Together with our parents and teachers, we organized public talks and protests. We also lobbied the faculty to create a Black history course.

In my area, the social atmosphere was mostly subtle racism … I was protesting the racism.

Our generation were social activists at a very young age …That was so important to my life. … I was working with the Black Panthers’ food programs before and after I became Baha’i.

Clergy seldom supported the noble protests of Black people about their treatment in America.

International crises arose, such as the United States naval blockade of Cuba because Soviets placed nuclear missiles there aimed at US targets. Future Baha’is were paying attention:

One of my defining moments was during the Cuban missile crisis — we would walk to school wondering where to build our bomb shelters. I wondered why we hated the Russians and decided I would someday go talk to them, so I started studying Russian — our school actually offered it in sixth through twelfth grade.

The decade spawned the war in Vietnam, which ravaged the lives of young American men who were drafted and sent on nebulous missions in chaotic jungle terrain. They returned home with stories of hellish anarchy and suicidal missions, along with a new commitment to oppose war:

… my generation realized we were being used. Americans had always wanted to believe we lived in the most perfect and just country in the history of the planet [which] is what we were constantly told, except by a few protestors popularly labeled fools …

I couldn’t even imagine the horror of anyone that was drafted. There was a very strong sense of dread when becoming draft age. They didn’t even know what they were fighting and dying for. The Vietnam war was a big part of our life.

Respondents lamented how their churches ignored the war and the racism that seemed to be devouring the country. They expressed dismay over clergy who voiced support for the war:

I was dismayed … by the political war support of Christian clergy who seemed not to care about the fate of the young men of my generation … my closest friends had come back deeply wounded mentally and physically.

Many intuited that there must be a pathway to world peace and love, and searched independently, prompted by a feeling that answers would be available:

From when I was around nine or ten years old, I used to walk to my hometown library to check out books attributed to Buddha and Krishna and also Zen thinking, because I felt moved to find out if those writings provided any clues, any wisdom, about life.

RELATED: Forging a Path From Mexico: The First Latino Baha’i Community

Those who searched for answers often objected to the magical thinking they’d encountered in churches, and others felt deeply troubled by religious leaders who couldn’t answer their questions:

I loved Jesus and identified as a Christian, but at seven I was ‘excused’ from my Presbyterian Sunday School after suggesting that if the Magi who visited the infant Jesus were — as our teacher explained — priests of another religion, then God’s truth must have been given other Faiths.

Previously, the Baha’i Faith had been relatively unknown in the United States, and embracing it often seemed like a daring step. Some future Baha’is first heard of the Faith from classmates:

I was taking a World Religion course and it occurred to me that to solve the world’s problems, everyone should have the same religion. Making that statement to about the only person in the enormous cafeteria at the time, I got this reaction: ‘Are you a Baha’i?’ At first, I rejected it outright. When I realized what the implications were that Baha’u’llah was the return of the spirit of Christ, I went ballistic.

Other accounts focused on the mystical aspects of the Baha’i teachings, like this one which describes the effects on a visitor at a Baha’i fireside gathering:

The feeling in that room was powerfully uplifting like nothing I had experienced before. In fact, I experienced that same extraordinary feeling, which I am not certain was the Holy Spirit, over the next few months which convinced me, even more than the beautiful and very logical writings of the Faith, that Baha’u’llah was indeed the Promised return of Jesus.

Many respondents reported experiencing dreams, coincidences, and premonitions that led them to the Baha’i Faith:

… one night, I was just talking to God and saying something like, ‘I wish there was a religion that taught that all of these religions had come from God.’ Literally within a few days of that ‘prayer’, I ran into a Baha’i who spent two or three hours talking to me about his religion.

After this girl learned about the Baha’i Faith at age 14, it changed her behavior so thoroughly that her mother was astonished — and also became a Baha’i:

I’d call [becoming a Baha’i] an awakening … I made drastic changes right away, but it was not pushed on me. I had sought it out … It was like being reborn. I put away pot, etc., became chaste, started listening to my parents. My mom even joined the Faith, after seeing my turnaround.

This man could feel a spirit emanating from a house on the street where a Baha’i fireside was being held:

The Holy Spirit was so tangible that people walked off the street to ask what was going on there. There were 20+ people of all ages and types and colors — hippies, students, working people aged 18-40 — which for me was unusual enough, but the feeling in that room was powerfully uplifting like nothing I had experienced before.

Asked about the reasons for remaining in the Baha’i Faith, this respondent said:

… the Holy Spirit, which the [Baha’i] writings make easier to bring to mind, is the most convincing and powerful proof of the validity of faith in God, in this and in all of the inspired dispensations of His prophets.

When these children of the 1960s encountered the Baha’i teachings, the social upheaval going on around them compelled further investigation — and the Baha’i Faith expanded rapidly.

Source link

6 Things You Should Look for in a Lasting Spiritual Relationship

It can be hard to know what spiritual qualities you should look for in a romantic partner when our media and entertainment industry bombards us with so many images of toxic, abusive, and superficial relationships.

That’s why I reached out to three Baha’i couples who have had healthy, long-lasting marriages for over 40 years and asked them to give singles their advice about what they should look for in a relationship.

1. Look for a Life Partner Who Has Many Virtuous Qualities

My mother, Barbara Talley, has been married to my father, Gile Talley, for 44 years. While they were dating, she realized that he was the nicest man she had ever met. They continue to be kind and respectful to each other four decades later.

That’s why she told me to look at a potential partner’s virtuous qualities first. “It’s nice that he or she is fine, but you will never find your soulmate if you’re not looking at their soul,” she says.

Susan Troxel, who has been married to her husband, Rick Troxel, for almost 46 years, agreed that the character of the person you’re thinking about marrying is most important. She advised singles to see if their romantic interest is truthful, trustworthy, kind, and compassionate.

RELATED: What Is Love? Defining a True Baha’i Marriage

Susan wrote, “Physical beauty fades for all of us, but the qualities of the soul are lasting. There needs to be respect and mutual support for each other’s spiritual pathway. It’s good to look at a prospective mate’s relationships with family and friends, as well as how they handle money. And very important is how they handle tests; are they willing to look at their own part and not blame others? Are they willing to sit down and pray and talk things out? Are they open to learning from their mistakes?”

My mom added, “We have guidance [from the Baha’i writings] to be pure, kind, and radiant and writings against being kind to the liar, the tyrant, and the thief, so don’t marry a liar, a tyrant, or a thief. If they are not kind and trustworthy, it’s a deal breaker. Keep that in mind before you take that vow.”

Since people are often on their best behavior during the courting phase, my mom says singles should also look at their prospect’s relationships with those who are close to them. “Find someone who treats their parents and siblings with respect. You’re marrying into a village,” she says.

As Abdu’l-Baha, one of the central figures of the Baha’i Faith, wrote:

BAHÁ’Í marriage is the commitment of the two parties one to the other, and their mutual attachment of mind and heart. Each must, however, exercise the utmost care to become thoroughly acquainted with the character of the other, that the binding covenant between them may be a tie that will endure forever.

“Remember that the journey of life is long and fraught with many surprises and ups and downs,” wrote Dr. Lameh Fananapazir. He has been married to his wife, Karen Fananapazir, for 49 years. “Your focus must be lasting virtues…Be clear-eyed and aware that time is not going to improve a flawed and unspiritual character.”

2. Look For Someone You Can Have a Spiritual Relationship With

When you find someone who has those virtuous qualities that you are looking for, it’s easier to establish a spiritual relationship with that person. Abdu’l-Baha wrote that “husband and wife should be united both physically and spiritually, that they may ever improve the spiritual life of each other, and may enjoy everlasting unity throughout all the worlds of God.”

So, Karen asked singles “to look for someone you can love and trust and who in turn also places his reliance and trust in God.” As you two strive to better the world and grow closer to God together, you ultimately grow closer to each other.

3. Find Someone You Are Physically Attracted to

Although physical beauty can fade, my dad says that physical attraction is important in a romantic relationship. Abdu’l-Baha wrote, “As for the question regarding marriage under the Law of God: first thou must choose one who is pleasing to thee…”

We should look for a romantic partner who is pleasing to our eyes and soul, because marriage is a physical and spiritual relationship. Everyone deserves someone who sees both their inner and outer beauty.

4. Find Someone You Are Compatible With

“Beyond the prerequisite attraction and affinity,” Rick suggested that singles seek “deep, nurturing compatibility, and commitment.” He listed several helpful questions that each new couple should ask each other:

- “How easy is it to be open, honest, and expressive with each other?

- Do you mostly share the same values, and respect and support even those you might not entirely share?

- Can you each commit to the same kind of relationship?

- How do you handle disagreements?

- [How do you handle] decision-making in general?

- Are you both of good character, in both deeds and words, in basically all contexts?

- Do you appreciate how your potential partner relates to others?

- Can you perform acts of service together and mutually support each other’s individual acts of service?

- When one of you is stressed (or joyful, for that matter), what does that bring out in the other?

- How well are you matched on what is viewed as stressful or challenging versus what is comfortable or adventurous/fun?”

Rick wrote, “Implicit in this, I guess, is to know oneself as much as possible, as holistically and integrated as possible. This facilitates the other’s investigation of you. It helps you distinguish your likes from dislikes, deep needs from more superficial desires, and where you can and can’t flex. It may help distinguish your true self from your social environment, upbringing, habits and customs, and popular trends.”

5. Look for Someone You Can Accept Completely

My mom says you shouldn’t look for a fixer upper that you intend to change to your liking. “It’ll put a strain on the relationship if you are going into it saying, ‘I don’t accept you for who you are, but if you become this other person, I will,’” she explained.

“We each have our path and will grow at our own pace or perhaps not at all. If you can’t accept the person fully for who they are now, then wait until you can find someone that you can accept.”

RELATED: Love: An Action, Not Just a Feeling

6. Marry Your Best Friend

“Lastly, look for someone who can be a very, very good friend — someone you feel you can talk to about anything,” Susan wrote. My parents say it’s easier to cultivate a close friendship when you have things in common, like similar values and lifestyles.

And, my mom says it’s also important to “find someone who makes you laugh.” Laughing together is a great way to bond two friends. It is physically and spiritually relaxing and can help get people through tough times.

As Abdu’l-Baha wrote, a married couple’s purpose must be “to become loving companions and comrades and at one with each other for time and eternity.…”

I hope this advice from older couples helps all of you singles out there find your eternal partner and forever friend.

Source link

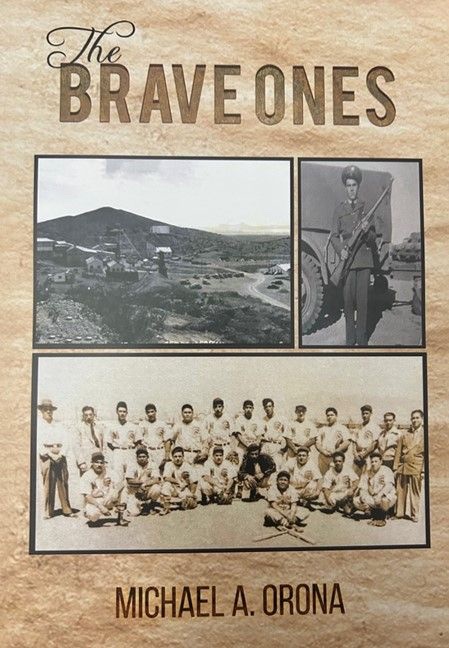

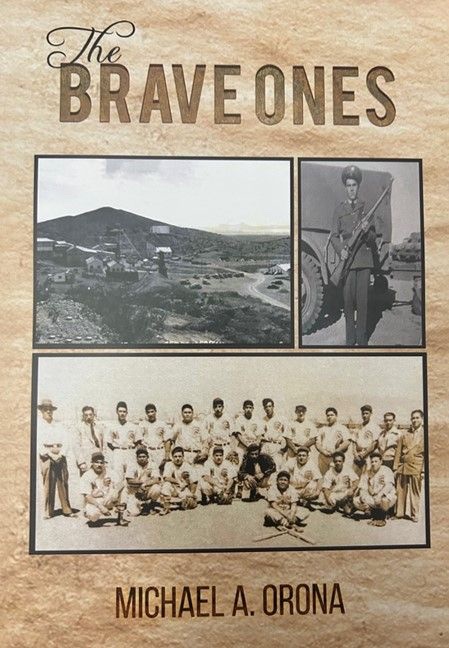

Lessons on Spiritual Courage: Reclaiming Native Narratives

In “The Brave Ones,” Michael Orona’s compelling narrative transcends beyond physical courage and delves into spiritual courage and resilience, highlighting the power of remaining steadfast in the face of oppression. As Baha’u’llah, the prophet and founder of the Baha’i Faith, wrote:

The source of courage and power is the promotion of the Word of God, and steadfastness in His Love.

Inspired by his personal experiences, family history, and the Baha’i teachings, Michael Orona discusses how the characters in his novel embody this spiritual courage and steadfastness, reflects on the ongoing fight for representation, and explores the lessons his book offers for today’s social justice movements.

Radiance Talley: Hi, Michael! The title “The Brave Ones” suggests acts of courage. How do your characters embody spiritual courage, and how does this align with the Baha’i view of steadfastness in the face of injustice?

Michael Orona: The title “The Brave Ones” carries deep spiritual significance that goes far beyond physical courage. It’s about a profound inner transformation and the courage to reimagine human possibility in the face of systemic oppression.

Spiritual courage, from a Baha’i perspective, isn’t about confrontation, but rather the ability to maintain dignity, hope, and foresight when every system is designed to break your spirit. My characters embody this through their refusal to be defined by their circumstances.

Consider the Baha’i principle articulated by Shoghi Effendi about the American believers’ special calling — to have the “moral courage and fortitude” to address fundamental issues facing humanity. The characters in the book live by this principle. They’re not just fighting against discrimination; they’re creating alternative models for the advancement of not only their own community, but also for the advancement of their oppressors.

The Indigenous peoples in the story — members of the Yaqui Nation from Sonora — represent this beautifully. They could have accepted their limited circumstances. Instead, they dream beyond their immediate reality and then act. Their dreams and the action to make them a reality symbolize hope — a spiritual act of resistance that transcends physical constraints.

Abdu’l-Baha’s teachings profoundly influenced how I conceived spiritual courage. He spoke about the Indigenous peoples of America having the potential to “enlighten the whole world” if properly educated and guided. My characters embody this — they’re not victims waiting to be saved, but transformative agents with inherent spiritual power.

“The Brave Ones” is a testament to this spiritual courage — a celebration of Indigenous peoples who refuse to be broken, who see beyond current realities to potential futures of unity and justice. I believe this embodies us as Native people, it’s who we are.

Radiance: Did you draw from personal experiences, oral histories, or Baha’i teachings on the value of diverse cultures?

Michael: The book is deeply rooted from personal experience, family narratives, and the Baha’i teachings that have shaped my life.

Growing up, I was steeped in my Indigenous cultural heritage in large part to the profound support of my late Apache father, Dr. Joel Orona, and my Yaqui mother, Esther Orona. Storytelling wasn’t just a tradition in our family — it was a way of preserving history, of maintaining cultural identity, and spiritual development. The oral histories my grandparents and elders shared with me as a child were living histories, not just personal narratives but collective experiences of resistance, resilience, and survival. It was through these stories that I was taught the importance of being of service not only to my own community, but to the global community. It was through these stories that I was reminded of the responsibility to honor the legacy of my ancestors.

As a child of the 1970s, I was acutely aware of the lack of diversity and limited representation of Indigenous peoples in the media. I remember watching television or going to the movies and rarely seeing people on screen who looked like me. Those rare times when Indigenous people were portrayed, it was done by non-Native actors in a demeaning manner. The watershed moment for me was watching Alex Haley’s “Roots” on television — a chronicle that brought the history of African Americans to the forefront. The importance of seeing the struggle and unique perspective from another marginalized community gave me hope that someday I would have the opportunity to share the historical challenges and success of my own people.

The Baha’i teachings were instrumental in shaping my perspective on cultural diversity. Baha’u’llah’s message on this topic was revolutionary, it was not about reforming existing social norms, but fundamentally shattering the very notion of racial superiority. This wasn’t just a social justice message, but a message of spiritual transformation.

Abdu’l-Baha’s teachings were particularly profound in the writing of the book. He spoke about the unique spiritual potential of Indigenous peoples, stating we will “enlighten the whole world” and serve as spiritual “standard bearers.” This isn’t patronizing but rather the sincere belief, acknowledgment, and recognition of the inherent spiritual wisdom found within Indigenous communities that have been historically and systematically marginalized.

Ultimately, the book is an embodiment of the Baha’i principle of the oneness of humanity. It’s not just about documenting historical struggles, but about creating a vision of human potential that transcends racial, cultural, and historical divisions.

Radiance: How do the themes of “The Brave Ones” resonate with today’s social justice movements? What lessons can readers draw from this historical narrative?

Michael: The story of “The Brave Ones” is not just a historical account, but a powerful lens through which we can understand the ongoing struggles for equity, solidarity, and human dignity. I believe the narrative of Indigenous peoples fighting for equality in partnership with African Americans speaks directly to the intersectional nature of social justice movements today.

First and foremost, the book illuminates the power of unexpected alliances. At a time of profound racial discrimination, these communities found strength in their shared marginalized experience. Today, we see similar dynamics in modern social justice movements — whether its organizations focused on Indigenous rights, economic empowerment, or struggles against systemic oppression. The lesson is clear: solidarity and collaboration across different marginalized communities is not just possible, but essential.

The book underscores how systemic discrimination creates seemingly insurmountable barriers. Members of the Yaqui community in the book faced limited opportunities, forced to live under difficult circumstances with little hope for advancement. This mirrors the ongoing challenges faced by Indigenous peoples around the world and other communities of color — unequal access to education, economic opportunities, and social mobility. Yet, the story is ultimately one of hope and resistance, showing how collective action can challenge and ultimately transform unjust systems.

Moreover, the narrative underscores the importance of telling our own stories. For too long, Indigenous peoples have been relegated to the margins of historical narratives, our experiences either silenced or misrepresented. “The Brave Ones” is part of a broader movement to reclaim our narrative, to center Indigenous voices and perspectives. This resonates deeply with contemporary calls for authentic representation and self-determination.

The themes of dignity, resilience, and a shared humanity are particularly relevant in our current social and political climate. We continue to grapple with historical injustices, systemic racism, and the ongoing impacts of colonization. The book offers a blueprint for understanding how communities can come together, recognize their common struggles, and work toward collective liberation.

I was inspired to write this story by the experiences shared by my grandparents and their generation — a reminder that our current struggles are deeply connected to historical experiences of oppression and resistance. The book is not just about the past; it’s a call to action for today’s generation to continue the work of building a more just and equitable society.

Ultimately, “The Brave Ones” teaches us that change is possible when we recognize our shared humanity, when we have the courage to challenge the status quo, and when we stand in solidarity with one another. It’s a message of hope that I believe is more crucial now than ever before.

Radiance: A reviewer mentioned that this story “finally broke the barrier” for Indigenous people to tell their own stories. What challenges do Indigenous authors face in having their narratives published and recognized, and how does the Baha’i Faith encourage perseverance in such efforts?

Michael: The publishing world has long been a gatekeeping system that marginalizes Indigenous voices. For generations, our stories have been told through a colonial lens — filtered, misinterpreted, and often romanticized or vilified by non-Indigenous writers. Breaking through these barriers requires persistent courage and a commitment to authentic storytelling.

Indigenous authors face multiple systemic challenges. First, there’s the structural inequality in publishing: limited representation in editorial boards, fewer publishing opportunities, and a publishing industry that historically prioritizes mainstream narratives. Many publishers view Indigenous stories as niche or unmarketable, failing to recognize the universal humanity and complexity of our experiences.

Our narratives are often expected to conform to stereotypical expectations — stories of trauma, historical suffering, or exotic cultural experiences that fit comfortable narratives about Indigenous peoples. But we are not museum artifacts or historical footnotes. We are a living, evolving people with rich, nuanced stories that speak to contemporary human experiences.

The Baha’i Faith has been instrumental in giving me the spiritual strength to persist. The principles of the Baha’i Faith, including the oneness of humanity, universal education, and the independent investigation of truth, are not philosophical concepts, but active guides for my writing and activism. The Faith encourages us to see beyond divisive boundaries, to recognize the inherent worth of every human being, and to work tirelessly for justice and understanding.

When I face rejection or encounter systemic barriers, I draw strength from the Baha’i teachings about perseverance. We believe that true progress comes through consistent, compassionate effort. Just as the members of the Yaqui community in my book refused to be defined by their circumstances, I refuse to let institutional barriers silence our stories.

The process of writing “The Brave Ones” was itself an act of spiritual and cultural resistance. By centering Indigenous agency, showing our community’s resilience, and highlighting our partnerships across racial lines, I’m challenging the dominant narratives that have historically marginalized us.

Moreover, my work is part of a broader movement of Indigenous authors reclaiming our narrative space. Indigenous authors have been instrumental in breaking down these barriers, proving that our stories are not just important — they are essential to understanding the full complexity of the human experience.

My Faith teaches me that every voice matters, that every story has the potential to bridge understanding. By persistently sharing our narratives, we challenge systemic inequities and create opportunities for genuine dialogue and mutual respect.

This is why “The Brave Ones” is more than a book. It’s a testament to the power of storytelling as a form of cultural preservation, resistance, and hope.

Radiance: Thank you, Michael, for sharing your profound insights and reflections. If you all are enjoying this Q&A, be on the lookout for part three where we’ll discuss practical actions we all can take to promote justice and harmony!

Source link

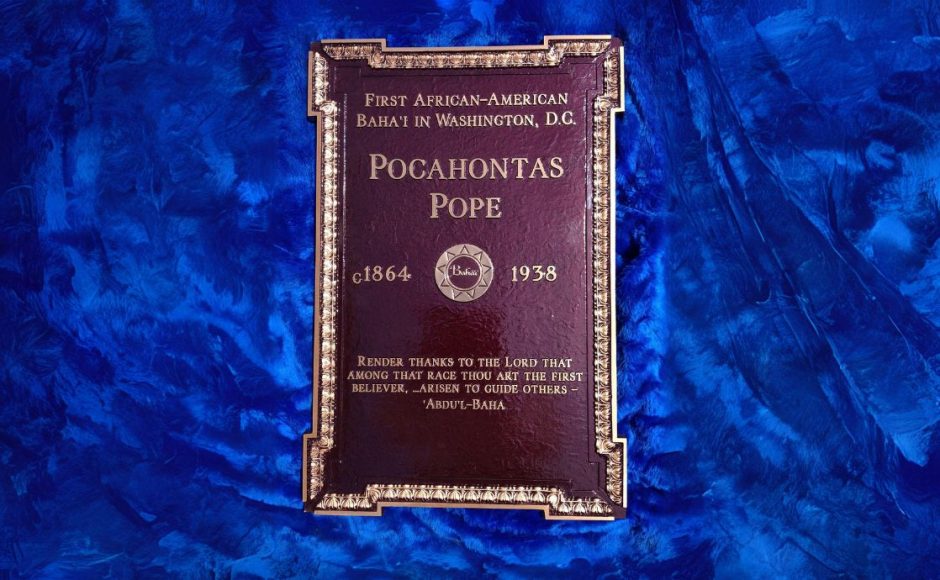

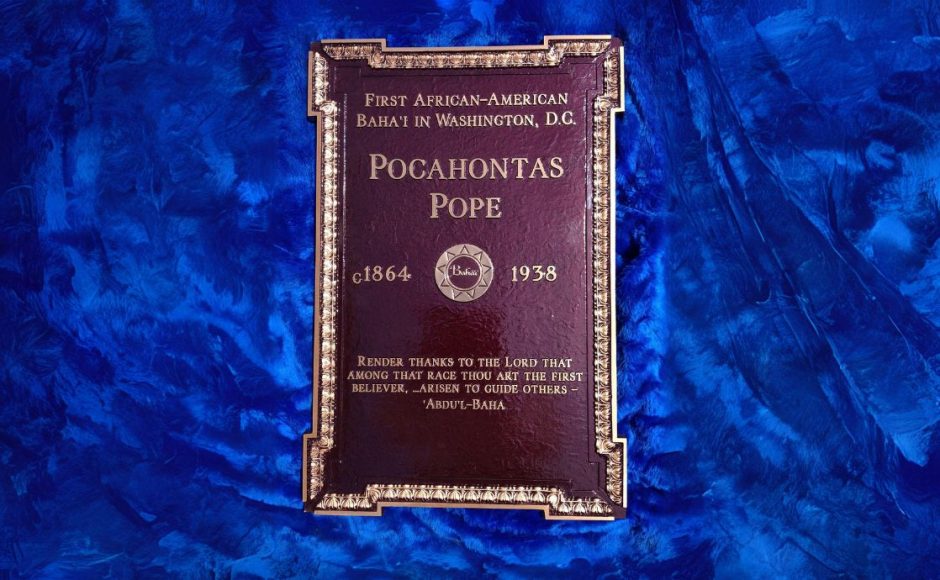

Do We Have Spiritual Ancestors? Meet Pocahontas Pope

We all have physical ancestors—but do you think we have spiritual ancestors?

Meet Pocahontas Pope, the first African American Baha’i of Washington, D.C., and a woman I think of as my spiritual ancestor.

A salt-of-the-earth, Black, former Baptist seamstress, Pocahontas Pope (c. 1865–1938) received a beautiful letter from Abdu’l-Baha, who drew upon Baha’u’llah’s “pupil of the eye” metaphor in a racially uplifting way.

RELATED: Invisible No Longer: Robert Turner as a Doorway to the Kingdom

Pocahontas’ family history (and ancestry) is difficult to reconstruct. Relying largely on the meticulous research of Paula Bidwell along with my own independent investigation, we can tentatively reconstruct Pocahontas’ background:

Pocahontas’ mother was Mary Cha, born Mary Sanling, and her father was John Kay. They married on January 11, 1861, and later had Pocahontas. Then, on November 11, 1876, Mary (Cha) Kay married Lundy Grizzard, who then became stepfather to Pocahontas. Lundy and Mary Grizzard went on to raise several children (Pocahontas’ step-siblings). Mary died in May, 1909.

On Dec. 26, 1883, John W. Pope (1857–1919)—born and raised in Rich Square, NC—and “Pocahontas Grizzard” married in Northampton (or Halifax) County, NC. John was 26. Pocahontas (née Grizzard) was 18. As to “Race,” each is listed as “White.” (Recall that the first African American Rhodes Scholar, Alain Locke, who became a Baha’i in 1918, was also listed as “White” on his birth certificate on September 13, 1885.)

Pocahontas’ husband, “J.W. Pope,” was one of three “Managers” of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Rich Square, NC, in 1896–1897. As an institution, the venerable AME Church is the oldest living African American organization. In summer 1898, John and Pocahontas moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked for the U.S. Census Office. But, in early 1902, he was fired by Director Merriam, along with other “Negro clerks.” John Pope landed a job in the U.S. Government Printing Office.

In June 1902, John W. Pope was elected first vice-president of the “Second Baptist Lyceum,” and Pocahontas Pope as assistant recording secretary. Established in 1848, the Second Baptist Church is one of the oldest African American congregations in Washington, D.C. Pocahontas Pope was described as “intensely religious”: “Even among our own race the woman with a past is intensely religious.” (The Colored American, 21 March 1903, p. 16.)

The Rev. John W. Pope died on March 30, 1918. Fast forward to 1920: according to the United States Census, 1920 “Pocahontas Pope” is listed as “Widowed.” As to “Race,” she is listed as “Mulatto.” According to the United States Census, 1930 “Pocahontas Pope” is classified as “Negro.” Pocahontas Pope died on November 11, 1938, in Hyattsville, Prince George’s County, Maryland. She is buried in National Harmony Memorial Park Cemetery.

In 1906, Pocahontas Pope became a Baha’i. This is how it happened:

Pauline Hannen was a white Southerner who grew up in Wilmington, NC. In 1902, she became a Baha’i in Washington, D.C. There, her sister, Miss Alma Knobloch, employed Pocahontas Pope as a seamstress. Then, as fate would have it, Pauline chanced upon this this passage from Baha’u’llah:

O Children of Men! Know ye not why We created you all from the same dust? That no one should exalt himself over the other. Ponder at all times in your hearts how ye were created. Since We have created you all from one same substance it is incumbent on you to be even as one soul, to walk with the same feet, eat with the same mouth and dwell in the same land, that from your inmost being, by your deeds and actions, the signs of oneness and the essence of detachment may be made manifest. Such is My counsel to you, O concourse of light! Heed ye this counsel that ye may obtain the fruit of holiness from the tree of wondrous glory. – Baha’u’llah, The Hidden Words, p. 20.

This passage struck Pauline in a lightning flash of sudden insight. After realizing the profound implications of Baha’u’llah’s words regarding the oneness and equality of the human race—in the singular—this is what happened next:

One snowy day, during the Thanksgiving season, Pauline came across a black woman trudging through the snow. Pauline noticed that the woman’s shoelaces were untied. Arms full from the bundles she was carrying, the woman was unable to do anything about it. Inspired by this passage from The Hidden Words, Pauline knelt down in the snow to tie this woman’s shoes for her. “She was astonished,” Pauline recalled, “and those who saw it appeared to think I was crazy.” That event marked a turning point for Pauline: she resolved to bring the Baha’i message of unity to black people. — Christopher Buck, Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy (2005), pp. 37–38.

RELATED: The Black Pupil of the Eye: The Source of Light

By July 1908, fifteen African Americans had embraced the faith in Washington, D.C. In a letter dated May 1909, Pauline Hannen wrote:

The work among the colored people was really started by my sainted Mother and Sister Alma [Knobloch,] though I was the one who first gave the Message to Mrs. [Pocahontas] Pope and Mrs. Turner. My Mother and Sister went to their home in this way, meeting others, giving the Message to quite a number and started Meetings. Then my sister left for Germany where she now teaches, I then took up the work. During the Winter of 1907 it became my great pleasure with the help of Rhoda Turner colored who opened her home for me… to arrange a number of very large and beautiful Meetings. Mrs. Lua Getsinger spoke to them here several times at Mrs. Pope’s as Mirza Ali Kuli Khan, Mr. [Howard] McNutt and Mr. Hooper Harris spoke in Mrs. Turner’s home. Mr. [Hooper] Harris spoke at Mrs. Pope’s [at] 12 N St. N.W. for my sister before his leaving on his trip to Acca and India. Mr. Hannen also spoke several times. My working to being to run around and arrange the meeting. At these Meetings we had from twenty to fourty [sic] colored people of the intellectual class. – Qtd. in Buck, Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy, p. 38.

The next article will describe, in detail, the “Tablet”—or special letter—from Abdu’l-Baha to Pocahontas Pope.

Special thanks to Steven Kolins for his research assistance.

Source link